Kazakhstan Bets Big On China's Silk Road

The jury is still out about China’s One Belt One Road development project. But Kazakhstan isn’t too worried. If there is one country in Eurasia, if not the world, that is more gung-ho about the new Silk Road to Europe, it’s these guys.

Should the government play its hand right, and with very little opposition to President Nursultan Nazarbayev’s reform agenda, there is no indication that it won’t – eventually -- Kazakhstan (KZ) will graduate from a “frontier market” designation on the MSCI global fund indexes to become the first emerging market in the ex-Soviet ‘Stans.

“I think that they are the next one to join the MSCI Emerging Markets Index,” says Babek Hafezi, CEO of Hafezi Capital, a McLean, Va based consultancy with about 35% of its clients coming from emerging and frontier zones like KZ. “If they keep improving their education system and their students that are going overseas come back home, and Kazakhstan captures that brain power, and if you can be at global standards of corporate governance, then there is no reason why this won’t become a more tradable market.” Pakistan got the greenlight to join the MSCI Emerging Markets Index in May.

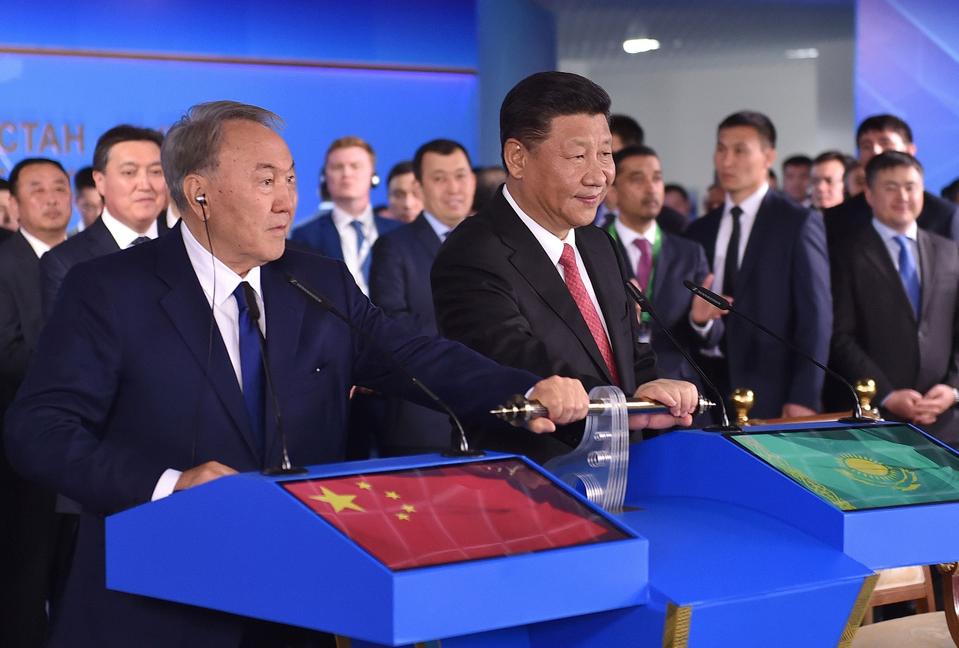

Kazakhstan is the most developed ex-Soviet ‘Stan. Its leadership has always been interested in going their own way. This time, their way is pointing to China – and beyond. It is perhaps the single biggest game changer for them. Kazakhstan is using China’s One Belt One Road as a means to light a firecracker under its own business and political class.

As it is, Kazakhstan’s investment grade economy is bigger than every single ex-U.S.S.R. state outside of Russia, only without the headline glamor. They’re bigger than the three Baltic states combined in terms of GDP, and KZ’s economy is twice the size of Ukraine’s. Its GDP is bigger than all other ‘Stans that were part of the U.S.S.R.

Either the next three years will see the passing of significant, more market friendly reforms (including a new stock exchange and, privatizations), or it will prove to be another disappointment.

"There are a million voices trying to get this government's attention and at the top, people are saying the right things. Measuring progress has been difficult," says Zach Witlin, an analyst with the Eurasia Group in Washington.

On one hand, the general consensus is that KZ has not yet successfully moved away from being a one trick pony insofar as it is dependent on natural resources. The President and the Government have declared this as the top priority, and do so every chance they are in the same room with Western leaders and investors. On the other, there is the view that KZ will move faster on reforms than other countries in the region.

"On doing business, I'd compare them to Russia," says Witlin. "On pushing the reform agenda, regardless of implementation, I would rate KZ higher. If we are talking about trajectory, then even in two years I think you would have seen more economic reforms in Kazakhstan than in Russia."

Russia is much more developed than Kazakhstan, so they are starting from a lower base. Both countries share a stubborn over-reliance on commodity exports to fund their government. Russia is ahead of this game. Kazakhstan is just getting in on it, prioritizing other sectors like biopharma and digital technology.

A New Market Begins To Form In Central Asia

For the next two months, millions of mostly Kazakh locals and some tourists will be visiting the Expo in Astana, the country’s second largest city. The Expo 2017 is part of the World Expo system, the same one that brought us the Eiffel Tower and Chicago World Fair. The government built an Epcot-like, futuristic facility to house different country pavilions. But Expo 2017 has its own modus operandi beyond its future energy thematics. This is about showing Kazakhs that they are part of the big world, and vice versa. When the Expo is over in September, part of the facility will be converted into the Astana International Financial Center (AIFC) and the International Center for Development of Green Technologies and Investment Projects "Future Energy". AIFC will house the Astana International Exchange, KZ’s modern stock market. Multiple IPOs are scheduled for next year. Kazakhstan will be privatizing major companies, including Air Astana and Kazakhtelecom, at some point in 2018 - with the government retaining the controlling stake.

“At first glance, the Astana International Financial Center looks staggeringly ambitious,” says S. Frederick Starr, chairman of the Central Asia-Caucasus Institute at the Johns Hopkins University’s School of Advanced and International Studies and the author of “Lost Enlightenment” --- a book about Central Asian history. “They want to become the trusted financial center between Shanghai, Dubai, and London. You can list 10 reasons why it will fail, but there are at least 10 reasons why it won’t,” he says.

One reason is there is currently no trusted platform for international financial dealings in the region, let alone one that is based on British law as AIFC will be. Moscow isn’t based on British securities law, but Dubai is. Both Hong Kong and Singapore are, as well.

“They may have come up with an ingenious proposal,” says Starr. He says the financial center’s chief executive, Kairat Kelimvetov, is a “highly competent” chief executive who has the brain trust behind him to build an honest-to-God financial capital in the middle of absolutely nowhere. “If Kairat can engage regional players, and not shut them out, then Astana can become a Central Asian finance hub,” he says.

It’s a step in the right direction for a country whose leadership is juggling many balls and even a few chainsaws. It has to make sure that this country of 18 million isn’t totally reliant on the economic growth of Almaty and Astana. Only about three million people live in those two cities. It wants to move away from being a raw material play, even though that is what mainly attracts the Chinese.

When three years ago the government announced that foreign investors in non-energy sectors would receive a 10-year tax break on corporate and land taxes in Special Economic Zones, transportation and logistics were listed as a priority. They forecast a need for some $26 billion over a 10 year period. China loves this sort of thing because one of the reasons why they have such a hard time exporting to their neighbors is because their neighbors don’t have the infrastructure to transport goods beyond a port.

So within a short period, the latest China mega project was born: the Khorgos Gateway. It’s a container port that connects Kazakhstan to China by rail right at the border. A Google Earth view of Khorgos shows it all: factories and warehouses on the China side, vast land and natural resources and open spaces as far as the eye can see on the Kazakh side. Khorgos will enter the record books as the biggest dry port in the world.

Just two months ago, Kazakhstan sold a 49% stake of its Khorgos Dry Port to two Chinese companies, China COSCO Shipping Corporation and Jiangsu Lianyungang Port Co,which each owning 24.5%.

On the China side, Khorgos is positioned as the western Shenzhen, a huge transportation hub, which is expected to develop quickly because of trade with Europe. China thinks it will grow into a city with around 200,000 residents. Ansher Global Investment manager Wang Shudong said in a recent report for investor clients that financing for new trade and logistics projects along the new Silk Road will not be a problem, given the high interest in this region among more than 2,000 private equity and venture capital investment funds in China.

A 2014 World Bank report titled “The Eurasian Cconnection” by Cordula Rastogi and Jean-Francois Arvis, said that in terms of speed, and cost per mile, the China train through KZ offers an “unbeatable value.” All of this infrastructure depends on trade with China or trade between China and Europe with KZ as a gateway. In the future, as KZ develops its own market, then many of the products will be consumed at home.

“Financing is really the carrot that China can offer,” says Rayan Rafay, an ex-HSBC equity trader from Hong Kong turned private investor and co-founder of frontier markets consultancy, Investment Frontier in Toronto. “China gets secure access to KZ resources and promises that if KZ develops a port, which helps ship Chinese goods, they will get the financing to KZ banks. China did this in Laos for example, and that really helped the Laotian banks. Financing is a huge part of all of this agenda,” Rafay says. “Everyone tends to focus on the pretty infrastructure, but the big thing is financing. KZ banks will have access to Chinese capital and KZ companies can sell raw materials into China. And whether the Chinese turn that into a product that’s sold in China or shipped back through Khorgos to Europe, either way, Kazakhstan benefits.”

Kazakhstan’s new Caspian Sea ferry port, known as Kuryk, was funded in part by Chinese capital. It launched this year with a million tons of cargo expected in 2017. The goal was simple: Kuryk makes it possible to triple KZ’s existing ferry capacities, available through a nearby port of Aktau, and strengthens the Kazakh section of the China-Europe transport corridor.

Kazakhstan is seen as an economic pioneer in an otherwise undeveloped part of the world that was once part of the old Silk Road. During that early period, that East-to-West route was as sophisticated as any in its time and got wiped out for a variety of reasons, not to mention infighting between religious sects in the Muslim majority region.

But now, the Silk Road is back. KZ is taking advantage. Since 2014, some $20 billion in Chinese investment has poured into KZ, with around $8 billion this year.

On June 20, Kazakhstan signed an agreement with the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) as an oath to government transparency and improving the investment climate for foreigners.

“Working with the OECD has helped us to prioritize our strategy for improving the investment policy framework with the objective of making Kazakhstan a better place to invest and to live,” says Yerlan Khairov, Vice-Minister for Investments and Development.

Adamas Illkevicius, a Lithuanian-born advisor to KZ’s national wealth fund called Samruk-Kazyna, says Kazakhstan is basically still building a nation for itself. “Most of my life was in different projects that involved one or another type of change: taking something and making it different from what it was,” he told Wade Shepard, a Forbes freelancer and resident Silk Road expert. “Delivering change is my specialty. I've done it in the West, I've done it in the East, and Kazakhstan is one of the countries that want to have both.”

Lithuania, by comparison, largely shunned the East. They embraced the West, joining NATO and the EU in 2004, and the euro in 2015.

Kazakhstan is taking a different tack. It takes a multi-vector approach to foreign policy, designed to shield it from too much China, too much Russia, and maybe even too much America. But for such a young country – Astana and Almaty 20 years ago were nothing like they are today – the only way for them to grow is to open up to the major countries that have already grown. Other than China and Russia, the rest of the world is far, far away. To entice investors to go to Kazakhstan, they need to continue to reform their economy in the ways they have promised they would under Nazarbayev’s now famous 100 concrete steps policy.

It’s going to be…

A Hard Row To Plow

In the slow world of multilateral agencies, OECD’s June 15 investment policy report says much needs to be done in order to fulfill Kazakhstan's ambition of joining the top 30 most advanced economies by 2050. OECD lists clearer strategies for attracting investments; reinforcing linkages between foreign and domestic businesses; ensuring a fair level playing field among firms; and effective promotion and enabling of responsible business conduct should be part of KZ’s goal of economic diversification, sustainable development and broader social progress. They also said judicial independence and corruption are the main concerns for businesses operating in Kazakhstan.

In the faster-paced world of markets, investors are interested. All of the big emerging market firms have their eyes on Kazakhstan and have bought their bonds. BlackRock owns them. JP Morgan owns them. A few weeks ago, Kazakhstan floated another bond in Russia, this one priced in rubles. It was oversubscribed.

Within the market place, the country’s biggest problem is oil and gas’ “new normal” price slump. Lower prices for hydrocarbons have hurt Kazakhstan more than most frontier markets mainly because their companies went on a spending spree in euros and dollars. “A lot of my clients were in real estate and they got killed from leverage in Kazakhstan when the Great Recession hit in 2008,” says Hafezi. “I think that was really the problem with Kazakhstan’s slow growth. They took on too much debt compared to their neighbors and the currency tanked.”

No comments:

Post a Comment

Comments always welcome!