China's execution orphans

Behind glitz of Beijing Olympics China hides a shameful secret..

thousands of children robbed of parents by their brutal regime

By Dan McDougall, XIAN, CENTRAL CHINA

The News of the World (UK)

June 15, 2008

|

On August 8 the eyes of the world will be on China as it glories in celebrating the pinnacle of human achievement in the 29th Olympiad. But behind that £2 billion spectacle lurks the hidden shame of man’s most callous inhumanity to man.

For China imposes the death penalty on more people than any other nation on earth—and then leaves the innocent victims left behind to rot.

A News of the World investigation has uncovered chilling evidence at Dhong Zou orphanage, 60 miles from the booming city of Xian, but a world away from all the hoohah of the Beijing games.

In the dusty courtyard, six-year-old Xieguntao digs his tiny fingers into the dry, grey earth as if trying to bury himself. Manic and restless, his hair matted and lice-infested, he rocks back and forward on his haunches.

Quietly, orphanage director Gou Gian Hou spells out the tragedy that brought the lad to this, revealing: “His father was caught felling timber on the land of a wealthy and influential businessman and was executed.

“His mother disappeared and the boy has been alone since he was three. Children are often just left behind at home when their parents are arrested. In remote areas they must fend for themselves.

“We found one eight-year-old cooking and cleaning in his house THREE MONTHS after his mum was taken away and killed.

“There’s such a stigma attached to the children of the condemned that they’re IGNORED by entire communities. Some die, others migrate to the city and are abused or become enslaved in child labour.

“It’s the lucky ones who end up in orphanages like this. Here they find a family among the others. The children help each other. They talk, cry, laugh and give each other therapy. They’re unique and together they’re stronger.

|

And if their future is bleak, the brutal manner of their parents’ death means their past is tainted too.

The laughter of four orphans swinging happily on a rusting climbing frame rings out as Hou tells us: “There are two ways the government executes people here in mainland China. They are either taken to a killing ground, a remote open grave, where a guard points a rifle at the back of their head and asks the prisoner to open their mouth so the bullet can pass out through the mouth.

Or they are dragged into an ‘ambulance’ and finished with a cocktail of three drugs—sodium thiopental to make them unconscious, pancuronium bromide to halt the breathing and lethal potassium chloride to stop the heart.

“Lethal injection is becoming more and more common, and that’s how they kill them now.”

The blue and white mobile execution units, locally known as Death Vans, have rolled into Xian and many other cities in the last year. They attract far less attention than the traditional execution grounds with firing squads, often held in public in front of crowds. Like so much in China, the exact number of vans is a state secret. But Xian, with a population of 7.5 million, already has a dozen.

As well as the growing numbers of execution orphans, children’s homes across China are full to bursting—with dumped youngsters. Up to 100,000 each year.

Most are disabled, deaf, blind or born with cleft palates or misshapen limbs. Some just have the misfortune to be albinos. Then there are the healthy babies of unmarried mothers or those who fall foul of China’s strict ‘one child per family’ policy. But children of the imprisoned and executed face the worst fate—disgrace and exile to go with their loneliness and sense of abandonment.

Shunned in their villages and seen as having crime in their blood, they have no escape from their parents’ crimes.

They live in a highly punitive society where executions are publicised on posters, with a damning red mark beside each culprit’s fingerprint, name and offence.

Hou Yu Hang, 13, is just one of them. She swings her feet from a rusting bunkbed in Dhong Zhou Orphanage. On the walls are torn-out comic strips and magazine pictures of Japanese models.

In her hand she clutches a heartrending grainy photo of her mother on death row. “I’m waiting for her to come back and take me home,” says Hou.

Behind her a volunteer careworker casts her eye to the ground and wipes away a tear. Hou adds: “My mother was arrested for selling fake mobile phone SIM cards. She’s innocent and they’ll realise it. I’ve visited her in prison twice in the last three years. She cries every time she sees me. I show her my school work and photographs from the orphanage.

“I have friends here. I love them like sisters but I think of my mother at night, I see her in my sleep, in my dreams.

“I miss her stroking my ears. It’s one of my earliest memories, and she’d sing to me, too.”

According to orphanage boss Gou, the girl’s mum could be put to death any time. He said: “It’s common for the relatives NOT to be told when their loved ones are executed.

“They’re given no last visit, they just turn up at the prison and find it’s all over. We fear this will be the case with Hou’s mum, but what can we do to prepare the child?

“She asks to visit her every week. Her father is long gone and her future is bleak. Nobody will offer a job to the daughter of an executed woman.”

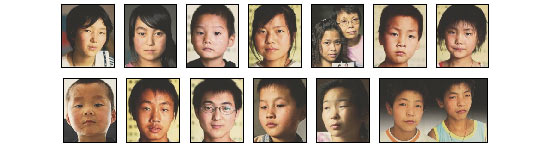

Here in the Xian orphanage there are 40 other cursed children like Hou, with parents either executed or damned on death row. It’s a picture repeated across the country thousands of times over.

And unless the rest of the world forces the Beijing government to clean up its act on human rights the numbers will continue to grow.

China still has the death penalty for SIXTY-EIGHT different crimes—from the heavy-duty murder and rape right down to VAT receipt fiddles, habitual theft, porn publishing, dealing in counterfeit money, backhanders, profiteering and killing pandas.

During our investigation we discovered men and women on death row for an unbelievable range of minor offences including communications workers selling private phone numbers to businessmen and minor thefts in street markets.

According to Amnesty International an estimated 374 people will be executed in China DURINGthis summer’s Olympics.

Official statistics claim a total of 470 were put to death here last year. But many campaigners are convinced the true figure is as high as 10,000.

Amnesty’s UK director Kate Allen said: “In this Olympic year China gets the gold medal for global executions.”

But it’s the callous lack of care for the orphans left behind that is truly shocking. Two months ago a small bundle in a grey blanket was left outside the Dhong Zou orphanage gates. It was a baby boy brought in by a concernced neighbour.

She had found the infant, crying and alone in a courtyard after police seized its mother from their remote village home. The children in the orphanage have taken the child as their own, taking turns to feed and hold him.

Like youngsters anywhere would, the kids play and cheekily stand to a mock salute in front of a faded poster of former leader Chairman Mao.

They laugh and giggle as they throw blackboard chalk at each other.

But all too often real life cuts in. Sitting apart from the rest, Li Na clutches a tear-jerking photo, the main picture on these pages. It was taken only moments before her father, a robber, was dragged off by the Chinese authorities to be killed. The picture shows Li Na and her brother clutching onto their dad’s arm in desperation. But the defeat clearly visible in Li Na’s face shows knowledge beyond her 13 years.

“This is the last thing I saw of my father,” she tells us. “He had his head shaved and he smelled funny. He was sobbing like a child and could barely lift his head.

“Some of the children here don’t know what’s happened to their parents. I’d prefer if that was the case with me, too. My dad fought them as we left the room, he tried to get to us through the glass. This is the memory I have to bear.”

As she talks, Li Na walks to the window and points to the fence surrounding the orphanage.

“That’s to stop the local villagers from getting to us,” she says sadly. “They see us as cursed and evil.

“But our parents’ lives are NOT ours. I don’t understand why they shout through the fence and spit at us as in the street. It makes me realise we all have no hope.”

Outside in the shade of the midday sun, the children queue up excitedly for bowls of noodles.

Xiong Ye, 13, is sitting alone. She is the most introverted of all the children there, after the trauma of losing both parents.

She saw her mother kill her drunken father after suffering years of abuse and violence.

For that the young mother was arrested, paraded through their home town then executed by a bullet through the head at one of the notorious execution grounds. Engaging tiny Xiong in conversation is difficult. But eventually she tells us: “Some people came to visit, counsellors.

“They wanted me to talk about my mother but I can’t think of her. All I have left is a small torn photograph. I have no other family and now I’m alone.”

As we ask what makes her happy she looks at the ground and seems close to tears. She adds slowly: “Looking at my mother’s photograph makes me happy.

“I take it to bed every night. I put it under my pillow. My dreams are for her, not for myself.”

Human rights activists fear the increase in lethal injections, which is inevitably followed by the harvesting of the victim’s organs, is boosting the country’s growing market for transplants. It is known that Chinese prison authorities have been trading in the organs of executed prisoners for two decades. So the mobile death vans can only fuel the grisly market, ensuring fresher tissue and more sterile facilities.

And China’s refusal to give outsiders access to the bodies of executed prisoners has only added to suspicions about what happens afterwards.

Corpses are typically driven to a crematorium and burned before relatives or independent witnesses can view them. We discovered at least 100 people in the ex-British territory of Hong Kong have been executed in the last five years—and relatives share doubts about the process.

In the darkened recesses of a Hong Kong apartment block stairwell Kwiho Wong, 36, clutches her husband’s death certificate and claims he was framed for trafficking fake pharmaceuticals.

The last time she saw him in prison was Christmas Eve. They were optimistic about an appeal. He put his hand against his 12-year-daughter’s as they spoke through the glass screen.

But in January he was executed without warning the family. They weren’t told for a MONTH.

Clutching her grieving mother-in-law Fungkwan’s hand, widow Kwiho adds: “I had no chance even to say goodbye. They just cremated my husband and sent me his ashes.

“We’re sure they took his organs. He was just 35 and healthy. His organs would have fetched a price. It’s the only explanation for the way they did it. They were covering up.”

Back at the orphanage Hou Yu Li Hang, 13 recalls how his mother suffered a similar fate. “I can’t remember my dad,” he says. “He left when I was young.

“My mother was executed for robbery but I remember how she used to buy me presents. She once got me a kite and I think of her watching me play with it in the street outside our house.”

Then, fiercely protective, he adds: “I don’t believe my mother committed the crimes the police said she did. She was a schoolteacher and a gentle woman who loved me and her neighbours. I don’t know why her life was taken.”

It’s clear Hou is the most resilient of the children at the orphanage, and it’s led to him becoming the house comedian. Against all the odds, his ambition is to be a drama star.

To prove his point he mimics our British accents then says: “I make the other children laugh and bringing happiness to others makes life so much easier for me.

“I WILL go to Beijing and become an actor. And I’ll become the first child of an executed mother to be famous, to rise to the top and make people realise we CAN have a life after what happened to us.”

No comments:

Post a Comment

Comments always welcome!